Door or detour? This is the question – and dogs know the answer!

Imagine yourself facing a dilemma in which a tempting treat is seemingly out of reach because between you and the reward, there is an obstacle. To make it even more tantalizing, the obstacle is made of transparent wire mesh, meaning you can see the treat just a few centimetres away – on the other side! Almost like a magnet, it draws your attention, but in vain, it cannot be yours.

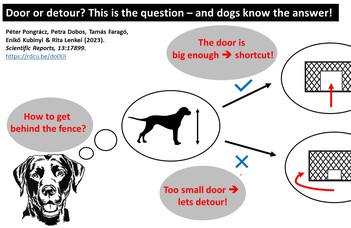

This problem is commonly known as the ‘detour task’ – because to reach the reward on the other side of the obstacle, at first, we would need to pry ourselves off of the ‘visually magnetizing’ reward and depart to the far end of the obstacle, turn the corner and return to the reward on the other side. Success! The detour is now complete.

But now imagine that on this fence, there is a door. When it is open, the reward can be easily obtained – no need for the lengthy detour. Who would not opt for such a splendid solution? Well, it all depends on whether that opening is big enough to allow a shortcut through it! But how to decide whether the opening is comfortably large or dangerously narrow? No one would like to get stuck when crawling through a too small door. It is easy to see that the above scenario is quite complex, which is unusual as behavioral experiments typically try to focus on only one factor at a time. However, this time, the ELTE Department of Ethology researchers tried to create an intentionally multi-layered experimental environment.

Ethology is the science of investigating behavior among ecologically valid conditions, and nature is very rarely as simple as experiments in a laboratory. Therefore, this time, dogs had to use their body-size awareness (the capacity to know how large you are) to solve a problem that had more than one solution. Reaching the reward was always possible if the dog detoured around the obstacle, however, making a shortcut through the door was a more optimal solution. If… the opening was large enough. Some of the dogs were shown a too small door – therefore, choosing this one would not provide a shortcut through the obstacle.

In this investigation, the main question was whether dogs would rely on their body-size awareness when it is only an alternative solution to the always available option to detour around an obstacle. The dogs at first had to master the task in which no open door was provided to them. Then, depending on the experimental group, either a large enough, or a too small door was opened for them.

According to the results, dogs mostly opted for the detour when they were facing the small door – they did not even try to get through the uncomfortably small opening. If the large door was open, almost all dogs used this easy shortcut instead of the more laborious detour. The difficulty level of the task was also detectable in a behavior that is very typical for dogs: looking at the human. When dogs face a difficult task, sooner rather than later, they start to gaze at the nearby human. In this experiment, the most frequent gazing occurred when dogs faced the closed door, thus they could solve the task only by detouring the fence. The next most difficult scenario was the small door. When the large door was available, dogs barely looked at the nearby humans – testifying that the task was easy.

And now, imagine one more thing… the world, as we see it, is pretty much the same as a short-headed dog would see it (such as a Boxer, a Pug or a Dogue de Bordeaux). Dogs with ‘normal’ head lengths have a different vision than ours – they see the world at a wider angle; however, they see things right in front of them with lower acuity. Would this difference affect the way dogs acted in the experiment? The answer is yes – longer headed dogs opted more often for the detour, while shorter headed dogs preferred to check out the doors first. The explanation for this is most probably the difference in how these dogs perceive the world around them.

This publication provides the first evidence that head shape can affect a dog’s behavior in a spatial problem solving task. It is also among the first investigations in which animal self-representation was tested in a complex, ecologically relevant situation. The study was recently published in Scientific Reports (https://rdcu.be/do0Ui). The author team included Rita Lenkei, PhD candidate, and Petra Dobos, MSc student, guided by the Department’s senior researchers, Péter Pongrácz, Tamás Faragó and Enikő Kubinyi.

Péter Pongrácz, Petra Dobos, Tamás Faragó, Enikő Kubinyi & Rita Lenkei (2023). Body size awareness matters when dogs decide whether to detour an obstacle or opt for a shortcut. Scientific Reports, 13:17899.